Ocean Acidification—What It Is, What’s Causing It, and What Can We Do?

Has this ever been a part of your life?

Taking a walk on the beach and picking up seashells? Or eating clams or oysters or lobsters? Or marveling at the beauty of the coral reefs of the world?

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is responsible for making those shells. But too much and the shells break down. Too little and the shells can’t be formed. It takes just the right amount of CO2 in seawater for ocean life to thrive.

But the oceans of the world are acidifying. That means they are becoming more acidic.

And it’s because too much CO2 is getting into the seawater. But how does it get there? Why is there too much? How does it acidify the ocean? What can we do to stop it?

What is ocean acidification?

When the ocean acidifies it means that the water is becoming more acidic and that makes ocean life less and less possible. It has drastic consequences for all life on this beautiful blue planet. (Remember, it’s blue because of the oceans on the planet and the life they contain!)

The acidity of liquids is measured on a pH scale that goes from 1 to 14. The strongest acid is at pH 1. Pure water is pH 7, which is neutral. And the strongest base is pH 14. Basic liquids are often referred to as alkaline.

An example of an everyday acid is lemon juice with a pH of around 2 or 3. An example of a base is an ammonia solution with a pH of 11. The pH scale is logarithmic like the Richter scale used for earthquakes. That means that a pH of 3.0 is an acid that is 10 times stronger than a liquid with a pH of 4.0. It also means that a pH of 3.0 is an acid that is 1,000 times stronger than one with a pH of 5.0.

Sea water normally has a pH of 8.2. It was that way for millions of years. But since the industrial age, it has decreased, and is now 8.1. That may not sound like a lot, but it is a 30% increase in acidity.

Projections of climate change estimate that by the year 2100, this number will drop further, to around 7.8…if we don’t change our ways now.

What causes the acidification?

Excess CO2 in the atmosphere is causing it. It’s absorbed into the water, often assisted by disturbance of the water’s surface from winds and waves. Once in the water, it forms carbonic acid. It also forms carbonate that reacts with calcium in the water, which the shellfish put together to make their shells.

But when more CO2 enters the water, more carbonic acid is formed. This pushes the chemistry to more acidity and less carbonate available for the sea animals to build their shells. In addition, the lower pH dissolves their shells.

demonstrate one way CO2 can dissolve

into water

CO2 has always been absorbed by the ocean. There are many chemical, physical, and biological reactions that absorb CO2 and use it and to put it back out. A stable balance has been occurring over millions of years that have allowed the beautiful ocean ecosystem we know to evolve and thrive.

But over the last 200 years humans have been extracting and burning fossil fuels that have been buried for millennia. This has been increasing the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere and the oceans have been soaking up about 30% of it. And it’s been acidifying the water.

In addition, large areas of deforestation have reduced the amount of vegetation that has been holding and soaking up CO2. Plus wildfires, with increasing frequency and intensity driven by extreme drought and heat events, have been releasing CO2 that was locked up and preventing more CO2 from being absorbed and locked up into the trees.

What does acidification do to marine life?

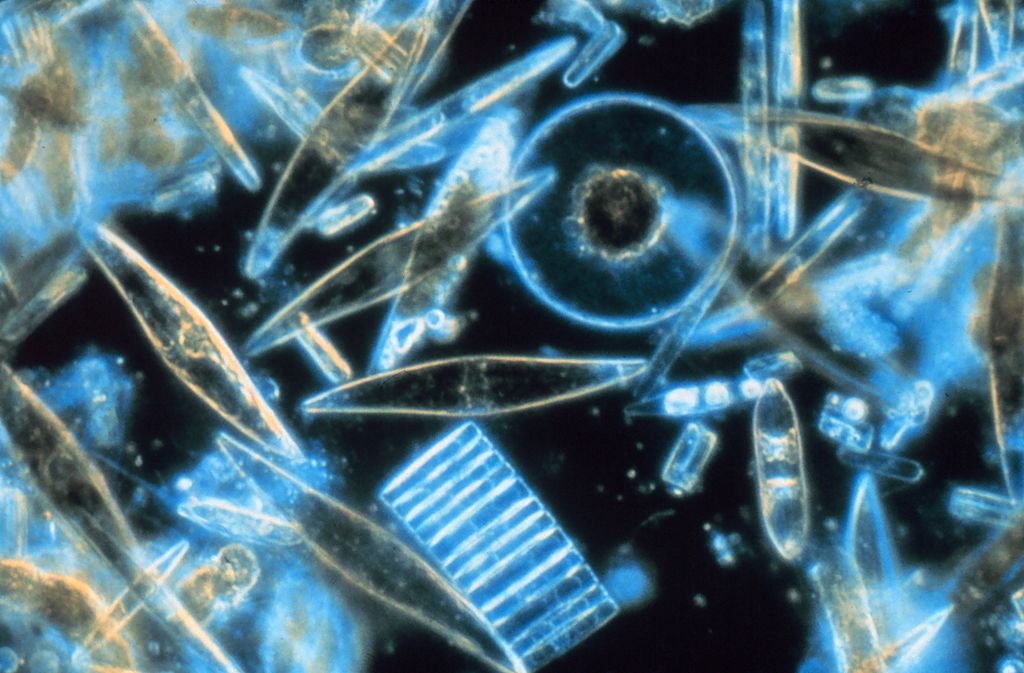

The base of the entire ocean food chain is plankton, tiny sea animals and sea plants, some microscopic. They’re the most significant source of food for all the other animals in the ocean. Without them there would be nothing. But they are sensitive to the pH of their environment.

Phytoplankton are the plants, only a few cells large, with no roots, that float freely in the ocean currents. Living near the water’s surface, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, other nutrients from the water, and with sunlight, grow, reproduce and feed larger animals.

And—they give off oxygen. Nearly 80% of our oxygen comes from phytoplankton. They are quite possibly responsible for making life on earth as we know it possible. Again, they are sensitive to pH of their environment.

Zooplankton are the animals: tiny snails, worms, krill, and even tiny young fish and jellyfish. They feed on phytoplankton and larger animals feed on them. Many whales require lots of krill to feed on.

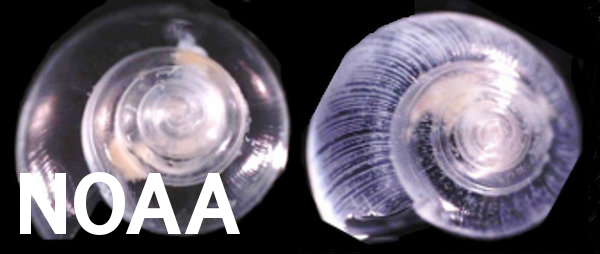

One pteropod, a sea snail zooplankton, caught scientists’ attention in the early 2010’s. Off the west coast of the U.S. they found that their shells were starting to dissolve. This was known to be a possible result of acidifying ocean waters but it was not expected to happen so soon. They found 53% of the pteropods had severely dissolved shells.

“Our findings are the first evidence that a large fraction of the West Coast pteropod population is being affected by ocean acidification. Dissolving coastal pteropod shells point to the need to study how acidification may be affecting the larger marine ecosystem. These nearshore waters provide essential habitat to a great diversity of marine species, including many economically important fish that support coastal economies and provide us with food.” ~ Nina Bednarsek, Ph.D., of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle

“We did not expect to see pteropods being affected to this extent in our coastal region for several decades” ~ William Peterson, Ph.D., oceanographer at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center,

“This is a surprising result. Effects of this magnitude were not anticipated this early in the 21st century.” ~Mark Ohman, a zooplankton ecologist who oversees a long-term research program examining the West Coast marine system for California’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, The Seattle Times

The pteropod is also called the sea butterfly because of wing-like flaps that allow it to swim the way a butterfly flutters through the air.

The shells on the beach and more

Later, in 2016, marine biologists studied Dungeness crabs from the U.S. west coast and found that they, too, showed damage to their shells. But also they found a loss of hair-like sensory structures the crabs use for balance, touch, and the ability to walk with direction and purpose. This occurred during their larval stage. Scientists had not expected these crabs to be vulnerable to that level of acidification.

“This is the first study that demonstrates that larval crabs are already affected by ocean acidification in the natural environment, and builds on previous understanding of ocean acidification impacts on pteropods. If the crabs are affected already, we really need to make sure we start to pay much more attention to various components of the food chain before it is too late.” ~ Nina Bednarsek, senior scientist with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project

Again, when ocean waters acidify, the carbonate ion from dissolved CO2 becomes less available to the animals that need it for making their shells. They must work harder and longer to find the materials they need at the expense of their growth.

And as the waters acidify shells’ calcium carbonate dissolves. This is what is happening and will happen to all shelled animals including corals, clams, oysters, shrimp, lobsters, and vital zooplankton like krill and pteropods.

What about the beauty of the ocean?

Can you even imagine walking along the shore and knowing there is no more life in the ocean? No shells, no seals, no whales to watch for, no seabirds at the shore?

Way back in 2009, Lisa Suatoni of the NRDC, Oceans Division., expressed this from a snorkeling trip with her children:

“I think about the dismay I felt last year when I took my kids snorkeling for the very first time on a coral reef in the Caribbean. I think about my kid’s utter delight at seeing a sprinkling of colorful fish and the occasional curious sea turtle, and about my horror at the terribly degraded condition of the reefs. I found myself faking enthusiasm a lot that week during those snorkels. I didn’t want to spoil their exhilaration with the reality that the reefs were a fraction of their former glory. This was the first time that I could so clearly see how my generation is denying the next of some of the great wonders of nature, and it was deeply disturbing.”

Her article was about the film “ACID TEST: The Movie: Why should we care about Ocean Acidification?” It’s an older film and things haven’t gotten any better.

photo credit: Shifaz Abdul Hakkim via Uunsplash

How can we possibly look our children in the eye and say we did not do everything we possibly could to prevent this from happening? We know about it and we have been warned. It’s crucial to act now.

What can we do?

The answer is simple yet difficult. Stop and even reverse climate change. The source of most of the excess CO2 in the atmosphere that makes its way into the oceans to acidify them is from burning fossil fuels. In our cars, heating and electrifying our homes, running our industries, and so on.

Demand your legislators to support climate policies. To stop the fossil fuel treadmill. And to expand cheaper, renewable, non-carbon-producing power supplies like solar, wind, and simple conservation. It can be done. Especially when the people demand it.

And model that it can be done. Solar energy is booming now, make use of it. The fossil fuel industry is subsidized, you, too, can get subsidies for installing cheap, clean, renewable energy for your home.

Support groups that educate and advocate for the oceans and for policies that reduce our impact on the oceans and climate.

Google “groups that advocate for the oceans” and “groups that fight climate change”, there so many to choose from.

There are volunteer opportunities, too, if you want to get physically involved in marine conservation. Check out opportunities at NOAA (my trusty weather source). And check Volunteer International HQ for more!

And here’s a fun one, see climatestore.com for awareness messaging stuff to show you care!

Support reforestation efforts to help soak up CO2. Even how we treat our soil in our gardens and landscapes can greatly enhance its ability to soak up CO2. (Read my post about that here.)

Do everything you can…there is no other Earth..

Related Reading:

Just What is Carbon Dioxide and How Does it Cause Climate Change?

Two Powerful Ways Soil Soaks Up Carbon Dioxide

What are Carbon Emissions?

Global Warming or Climate Change–Which is the Better Term?

How is a Carbon Footprint Calculated–and What do we do With it?

Great content! Keep up the good work!

Thank you, it’s good to hear that!